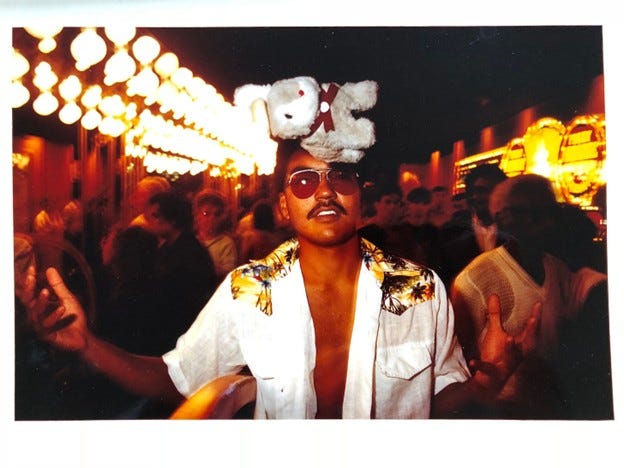

Dave and I made the decision to drive the 300 miles to Vegas as a sudden college nerd dare - I’d bought a toy bunny at the San Diego Sports Arena parking lot swap meet, then Dave stuck a small bagel on the bunny’s ear. We’d met at our college newspaper, where I was the features editor and Dave took pictures. He accompanied me to the swap meet for the potential photo op, and urged my toy bunny acquisition. As we drove out of the parking lot, Dave mused that it would be fun to take pictures of the bunny poolside at Caesar's Palace. I said sure, and as the sun edged into the Pacific, I veered the car toward the interstate onramp.

Three hours and 200 miles later we were in fifth gear doing about 90 in the nighttime sea-level desert flatness, the surrounding landscape lit phosphorescent-bright with moonlight. A summer storm ran parallel to us. I swapped out tapes on the cassette deck, swishing down the smoke of unfiltered Lucky Strikes with sips from a big gulp of Coke. We had no plan other…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Episodic to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.