I did all right in middle school but hated math and science because they required a monotonous precision that I could not bring myself to muster. I loved any subject involving reading because that was what I did when I was alone, which by my own choice was most of the time. I’d save my allowance to buy 98 cent books from pharmacies and discount variety stores – pocket-sized adventure and mystery paperbacks stuffed onto rotating black wire racks, usually with colorfully lurid cover art, churned out by mass-market publishers like Fawcett, Bantam, Dell, and Avon, written by Stephen King, Agatha Christie, Robert Ludlum, and Alistair MacLean – names never mentioned in future literature classes.

Alone in my room, I’d survey my growing library of paperbacks neatly aligned along the edge of the shelf next to my bed and feel a joyful love for their precisely rendered worlds. The spy stories and whodunnits offered what reality couldn’t: clarity of action and satisfying outcomes. I felt closer to those books than I did to my own family, and it was only a matter of time before my attachment became an obsession that would lead to my first literary crime.

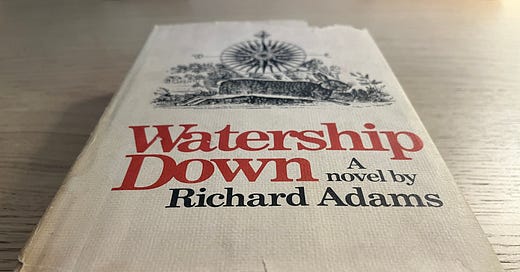

The book I intended to steal was titled Watership Down. It was about rabbits who go on a journey. I came across it in the library of my junior high school. Reading it was my first step away from genre fiction towards something more layered and deeper, with conflicted heroes who struggled to make more difficult choices. The rabbits in Watership Down were not cartoon or fairy tale bunnies – they had their own complex language, religion, hierarchy, and ethics. Books like these were the next phase of my exploration of life beyond the empirical – stories with more questions than answers. Some of us gravitated towards Asimov’s science fiction or Tolkien’s wizards to expand our minds. I went for the rabbits.

The book was a hardcover, with a beautiful two-page hand-illustrated map after the decorative title page, table of contents, and acknowledgements. I’d never seen a volume like this - compared to my flimsy paperbacks, the 400-page tome seemed to carry its own unique gravity, both literary and literally: I was impressed by its heft, and the aesthetic care taken in its construction – the rough texture of the weighty, bleached pages, the elegant readability of the serif font, and the grandeur of the chapter headings. The jacket flap featured highlighted accolades from notable critics and a halftone photo of Richard Adams, the author.

I went to the campus library to read this book every day during my free study period, tracking my progress with a bookmark I kept deeply wedged and out of sight.

The almost-blank card in the pocket on the inside cover revealed that the book had seldom been borrowed, and when it had, was not out long enough to be read in its entirety. I found it heartbreaking that this magnificent book would sit on a shelf, unappreciated. If it were mine, I would re-read and cherish it for the rest of my life.

To prevent the unlikely chance of it being checked out, I moved the book out of the fiction section and stashed it among chemistry books on a shelf in the back of the library, where I was left alone to lose myself in the story. After a few visits, I knew that it was not enough to borrow it - I had to have it forever. It was far too expensive for me to buy so I set my mind to steal it, which, considering my nascent passion, I rationalized as a liberation. I knew the school would not share my reasoning, so I’d need to get it out of the library without being discovered. That required a plan.

The building had a back door with a pneumatic piston that closed it automatically, triggering a latch that locked it from the inside. A key was required to get back in. This exit was accessed only by the custodians to haul the library’s trash to the dumpster. Students were forbidden from using it, so my doing so would be conspicuous. The passageway outside was largely out of sight, but for that reason the custodians liked to linger there. Slipping out the back door, I might run into them - with no way back in. I deemed it too risky.

I considered wrapping the book in a plastic bag, then tucking it into a wastebasket and retrieving it after the custodians had removed the trash from the building. But the dumpsters were kept near the parking lot, and a kid climbing into the filthy metal containers to root through garbage would draw too much attention from passing teachers and administrators. Anyway, even wrapped, the book could be discovered, damaged or stained - none of which I considered acceptable.

The students entered and left through the main doors, which required walking by a kiosk occupied by an adult. Mrs. Bryan, the heavyset, depressed red-haired librarian usually sat behind it, but barely paid attention to whomever was coming and going. Tom claimed he could tell by her posture that she was unhappily married, or possibly sexually frustrated - two subjects about which he had no knowledge. But because she seemed weak and vulnerable, he enjoyed mocking her, observing that her orange pantsuit and red hair made her resemble a fat, suicidal fire hydrant.

Between periods Mrs. Bryan exited the kiosk and left out the front door to slowly walk to her car while smoking a cigarette. Her fixation on the ring of the school bell to head outside and light up a Virginia Slim was Pavlovian, and I could take advantage of it by walking out the door behind her. I decided on this plan of action.

The next day, I slipped the book in my backpack and stuffed my cardboard pee-chee homework organizer over it, waited behind the shelves until one minute before the period ended, then made my way toward the door, conscious of the added heft on my shoulder. I became hyperaware of my movements and tried not to walk too fast, keeping my head up and eyes forward. If I were caught stealing the book, I’d be sent to Mr. Vowinkel’s office, and my father would be called. I knew my father was home compulsively trimming the plants around the house and didn’t leave to open our family’s restaurant until late in the afternoon. Getting the call from the vice-principal, he’d immediately come to school to pick me up and, after the humiliation of having to apologize for his son’s criminality, there’d be hell to pay on the drive home.

I walked towards the kiosk trying to affect casualness. Mrs. Bryan looked up at the wall clock and, craving her nicotine break, stood up from the kiosk stool, reached down for her purse and gathered her coat in anticipation of the ring of the bell that brought ten minutes of freedom. I quickened my pace to time my exit with hers, but as I was about to reach the kiosk, I saw behind her the door to the library open. In walked Mr. Rodrigues, Mrs. Bryan’s assistant. I stopped and watched Mr. Rodrigues slip behind the counter Mrs. Bryan had just vacated. Mr. Rodrigues was in his 20’s, was very smart, and liked to tease the suburban kids he monitored, frequently mentioning how he’d gotten streetwise from his rough upbringing in Barrio Logan. He favored high-collared chest-tight polyester long sleeved shirts and seam-tortured slacks with flared legs to accommodate his Chelsea boots. He prided himself on spotting troublemakers in the library, and I was certain that the moment he saw me he’d decode my guilty countenance, stop me with at “Not so fast…,” hammer me with a series of questions, then have me dump the contents of my bag on the kiosk counter.

My shallow bravado dissipated, I quickly walked to the back aisle, slipped the book back between the chemistry textbooks, then trudged back past Mr. Rodrigues and out the door to biology class. When I passed him, he didn’t even look up at me.

A week went by before I could build up enough nerve to try again. I continued to visit the book, following Hazel and Fiver’s escape from the copse at Nuthanger Farm. Reflecting on my failed first attempt, I convinced myself that my error had been improper timing - next Wednesday would be the best day to make my next run, when the library was usually busiest, and Mrs. Bryan and Mr. Rodrigues were occupied with tidying up the detritus left by the students.

As I entered the library Monday afternoon, two unfamiliar men were busy at the kiosk with a set of tools. They were installing what looked to be a flat metal bar on a pole next to the kiosk. The bar was waist-high and swung on the pole to block the passage next to the kiosk. Attached to the pole were red plastic lenses not unlike the taillights of a car. I sat next to Tom and asked him what was going on.

“Security gate,” he said.

“What for?”

Tom gave me a look of derision – his standard expression for any clarifying question directed at him. “What do you think? To keep people from walking out with books.”

I couldn’t believe it. I felt that someone must have found out about my plan, but I hadn’t told a soul - it was just bad luck.

I watched the workers finish their installation, then with Mrs. Bryan and Mr. Rodrigues observing, one technician waved a book in front of the sensors, causing a buzzer to sound. He demonstrated to Mrs. Bryan and Mr. Rodrigues that the bar was now locked, preventing the thief from leaving. The other technician leaned over the kiosk counter to press a switch that stopped the buzzing and released the metal gate. The librarians nodded in approval.

“It won’t work,” Tom said, not looking up from the piece of graph paper on which he was charting x/y coordinates for next period’s algebra class.

“Why not?”

“Because of where they placed those sensors.”

I looked again at the plastic lenses mounted on the post against the kiosk. “They look pretty good to me.”

Tom pointed his mechanical pencil toward the gate. “They’re facing one way. There’s a blind spot. They can’t see books behind them.”

“What do you mean?”

“Just what I said. All you have to do is pass the books behind it.”

Tom had no idea that he was offering me practical advice. I considered his point. But I’d need to swing my backpack behind the post while walking through the gate.

“It’d be too obvious.”

Tom snorted and got to his feet. Like me, he was all legs and arms, gangly and loose limbed, with no muscle to speak of - only pock-marked flesh stretched over rapidly elongating bones and diminishing baby fat. But unlike me, he was filled with a jittery energy that erupted in sudden bursts – a loud, cracking voice, a tendency to leap to his feet to make a point, and his jerky, arm-flailing gait. He’d developed a nervous habit of smacking the backs of his fingers against the palm of his other hand as he was thinking. It was all due to the flood of hormones coursing through our 13-year-old bodies, the inevitable pubescent calamity we could only endure. His impetuousness was sometimes hilarious, but it was usually annoying, because in addition to Tom’s tremendous intellectual prowess, he had a precocious sense for human frailties. He could tell I liked Marianne Seligsen, and when I stupidly admitted it to him at the Towne Centre Mall video arcade, he teased me mercilessly about it every day in home room, advanced english, and the library. We all were beginning to crave romance: the swooning rapture we read about, that was embedded in song lyrics and gloriously depicted in movies and on TV. Requited attraction was validation that we desperately desired, but obtaining it was going to be clumsy at best, and in the dreaded worst case, unobtainable, but only Tom reveled in the humor of our stumbling pursuit of it. He told Marianne of my feelings for her during gym class as they were waiting in line together at the racquetball courts. Afterwards, when she actively avoided me, he teased me even more. Despite his complete absence of discretion, I believed that Tom had told Marianne as a favor to me, but when it backfired, he wasted no time enjoying my rejection. He was cruel in a loving way, or his love was expressed cruelly. I could never figure it out.

Tom jumped to his feet, walked to a nearby bookshelf, pulled out a book at random and stuffed it in his backpack. He then walked to the kiosk and chatted with Mrs. Bryan. When she swiveled on her stool to speak to another student, Tom turned to make sure I was watching, then plopped his backpack onto the kiosk’s Formica counter. He grandiosely pushed the bar open and walked through the gate. After he passed through, he reached around the post and snatched his backpack, slid it along the counter behind the sensors, then walked to the front door, holding the backpack up so I could see it. He then turned to me wearing a shit-eating grin and walked back through the entrance side of the kiosk. Mrs. Bryan was still chatting with the other student and hadn’t noticed Tom’s demonstration. He walked back into the library, pulled the book out of his backpack, tossed it onto the desk and sat back down next to me. “See? Crappy design.”

Such behavior was easy for Tom because neither he nor his parents would care if he was caught stealing, which he did whenever the mood suited him – boxes of Jujubes lifted from the concession stand during matinees at the multiplex, Oui and Cheri porno magazines after school at the minimart, or as a joke, pens from friends – including mine – that he purposefully used in my presence. He’d return it without a fight when I’d noticed it, with a patronizing air of a sly perpetrator taking pity on his victim. Tom’s parents encouraged him to stroll through life with an enormous sense of entitlement – a luxury never bestowed to me.

The notion of asking Tom to steal my book for me entered my thoughts, but I immediately dismissed it because I knew he’d use it as blackmail for the rest of our friendship, and like he did within his inside knowledge of my feelings for Marianne Seligson, I’d have no guarantee that he wouldn’t exploit my secret for his own amusement. I knew he wouldn’t even care about incriminating himself because, like love, candy, porn, and pens – he was sure he could get away with it.

I got up from the desk, leaving him to finish his charting, chagrined by his unconcerned ease that came from a steadfast belief that he was smarter and better than anyone else in the world.

I spent the next few days sitting on a footstool in the back of the library turning the treasured book in my hands, wondering if I could get the nerve to do what Tom did so easily, but the image of my enraged father and the stinging humiliation of my getting caught paralyzed me. Summer break was approaching, and I would not be able to finish the book before it was entombed in the shuttered library, leaving me to ponder the fate of the rabbits for three long months. And if in that time the book was rotated to another school, my chance of owning it would be forever gone. This urgency stirred in me a powerful passion I’d never before felt, fueling my compulsive need for possession. I envisioned my happiness at seeing it on the shelf in my bedroom, standing out from the meager row of paperback novels and Peanuts comic books.

As I sat on the stool, I saw Mr. Rodrigues at the end of the aisle, sitting with a stack of books. He was opening each, then reaching into a small box on the floor next to him, inserting something between the pages and closing it. I got up and walked past him. The box held hundreds of tiny pieces of metal. These were what the sensor detected.

I waited for Mr. Rodrigues to move to the next aisle, then went to the books he’d put back on the shelf. I pulled one out and flipped through it until I found the little metal strip no bigger than a staple, tucked deeply in the seam between the pages. I tried to peel it off, but glue held it firmly in place. Once tagged, my book would be forever detectable, unless I committed the unconscionable act of tearing out the pages that held the strip. Mutilation was out of the question. I had to take the novel out immediately.

Ironically, since the installation of the gate, Mr. Rodrigues and Mrs. Bryan were kept so busy inserting the strips into the thousands of books in the library, their vigilance had plummeted. Now would be the best and only time.

I waited for Mr. Rodrigues to move to the next aisle, then stuffed the novel into my backpack. The bell rang. I got up and slung the backpack over both shoulders and made my way to the kiosk. Again, my legs became rubbery, and visions of my seething father being scolded by Mr. Vowinkel flashed in my mind. I forced myself to keep moving towards the kiosk. To overcome my fear, I reminded myself that the book was undetectable.

A loose line of kids had formed in the rush to leave the library, with each student having to pass through the gate and sensors. As I joined them, it occurred to me that the book might already have been tagged. I hadn’t searched every page. Maybe Mr. Rodrigues had already seen it hidden and tagged it to see who would attempt to steal it. My mouth went dry. My nerve lost, I decided to put the book back, but as I turned around, I saw Mr. Rodrigues standing at the back of the line, arms crossed as he watched the kids filter through the exit, his sly grin seemingly aimed at me. I was sure he’d stop me from heading back into the library, and even though I technically hadn’t stolen it, he might search my backpack and confiscate my hidden treasure.

I was one of the last kids to leave. My teenage hormone-fueled paranoia was rampant. I willed myself to keep moving towards the kiosk.

A little long-haired blonde kid in surfer shirt and shorts in front of me passed through without a care in the world. I breathed in, took a step forward, then reached out to push the bar open. I exhaled and walked through.

Nothing. No alarms, no adults rushing to me, no hands ripping the backpack from my shoulders, no stammering alibis, no Mr. Vowinkel’s office, no furious father called from his interrupted gardening to pick up his thieving son, no bellowed lectures on the drive home. I’d gotten away with it.

Stepping out the front door of the library, I couldn’t help breaking into a huge smile. The book on my back seemed alive. The rabbits were mine. I imagined them to be grateful and relieved. I kept my backpack on my lap for the rest of the day, and at school’s end I biked home in tenth gear, my shirt soaked in sweat as I pedaled as fast as I could.

That night I lay on my bed looking at the wide spine of the book on my shelf. By then my triumphant joy was gone. I was learning that the successful completion of a crime is quickly followed with the relentless fear of being caught. Earlier that night, as my mother brought laundered clothes into my bedroom, I stood up to block her view of the book. I knew I couldn’t behave like this indefinitely and worried that when my parents inevitably discovered the book, they’d ask who gave it to me or how I’d paid for it, forcing me into a string of lies I’d have to keep straight in my head for years, until I moved away for college or was sent to prison. Like a character from the Poe story, my guilt had become a living thing – instead of liberation, the book was now my captive, and its existence in my room was evidence of my moral corruption.

I used a razor blade from my brother’s shaving kit to carefully remove the check-out card sleeve, tore it and the card into tiny strips, then scattered them into the family trash can sitting on the curb in front of our house. Relieved that pickup day was tomorrow, I counted the hours until the city trash truck came to haul away the incriminating evidence.

Examining the book yet again, I was horrified to discover the school’s name stamped on the page edges at the top and bottom of the book – a detail that had escaped my prior inspections. Cursing my sloppiness, I cracked open my bedroom door and listened for my father’s steady snoring across the hall that confirmed my parents were completely asleep. I then quietly rushed to my mother’s office desk and searched frantically for her bottle of white-out. Relieved to find it, I snuck it back to my room, calmed myself to steady my shaking hands, then carefully blotted out the imprints of the stamps. I took the bottle back to my mother’s desk and placed it back exactly where I’d found it, then went to the kitchen and searched through the cookbooks in the cupboard until I found one with a price tag affixed to the flap of the dust jacket. I carefully peeled the price tag off and quietly scurried back to my room, then affixed it onto the dust jacket of my book. Examining my deception, I saw that the price of the cookbook was less than what the novel would cost, so, using an eraser, I carefully eradicated to the first digit of the price.

I slipped the book back on my shelf, exhausted from committing the first and only premeditated crime of my life, the brief triumphant joy of ownership forever gone. I spent the next few months in constant fear that I’d somehow be discovered, yet I could not bring myself to throw the book away, or worse - destroy it. Nor could I hide it - the magnificent novel deserved to be in full view, so it stayed on my bookshelf, where it’s been ever since, now a symbol of reckless, unreasonable love and lengths I’m willing to go for it. Not once have I ever re-read it, nor did I ever speak with Marianne Seligsen.

Wonderful. I suppose we all have a stolen book somewhere on our shelves.

Love!